Equity Crowdfunding Terminology

In today’s world, if there is a word or phrase you don’t understand, it is incredibly simple to put it into Google and – voila! – get the definition. Despite that, today’s post is meant to be a firehose of equity crowdfunding and early-stage investing terminology, to help give you the jump-start you need before diving into any deal.

After all – while still considered a type of investing – early-stage investing, via equity crowdfunding, is an entirely separate world from the domain of public stocks and real estate investing.

If you review this list just one or two times when starting out, it should help you out immensely when learning all the new jargon used in early-stage investing. And you are sure to encounter many new terms that we don’t have below, but this is intended to provide a solid foundation for getting started.

Let’s jump right in.

Also available as FREE video courses! Much of this is covered in Module 1 of our Level 2 Early-Stage Investor courses. The content is 100% free. Just create your account at CrowdWise Academy.

Deal Basics

Acqui-hire – an acqui-hire (acquisition+hire) is when a company buys another company primarily for acquiring its employees and talent. Typically, the product or intellectual property (IP) of the company is deemed not as important, and may be completely discarded in the acquisition; thus, it is not typically a desirable outcome for investors.

Due Diligence – due diligence is the undertaking of an investor, prior to committing capital to a potential investment, to confirm that all facts and other claims made by a founder and/or equity crowdfunding offering are true and/or not overstated.

Equity Crowdfunding – made possible by the JOBS Act of 2012, equity crowdfunding is the new legislation that eases securities regulations in key areas to allow the selling of equity in private companies to the general public. Also called crowdinvesting.

Exit – an exit, also known as a liquidity event, is an event (sometimes an option, sometimes an obligation) where an investor can cash out on their investment due to the sale of the business to another entity (e.g. a public company, private company, private equity firm, other investors, etc.). Typical positive exit events for early-stage investors include: initial public offerings (IPO), merger and acquisitions (M&A), private equity (PE) buyouts, and dividend, royalty, or buybacks.

Funding Portal – a funding portal is an online marketplace registered with FINRA, whereby private businesses can go to raise capital and investors can go to invest in these businesses. By law, funding portals cannot offer any investment advice or solicit purchases, sales, or offers to buy securities offered on their websites.

Internal Rate of Return (IRR) – the internal rate of return (IRR) is the interest rate at which the net present value of an asset’s cash flows (gains and losses) are equal to zero. Said another way, it is the annual interest rate earned on each invested dollar over the time period invested. It is a way of taking time into account when calculating returns on an investment, since gaining $100k on a $100k investment after 5 years (IRR=13.9%) is not the same as gaining $100k on a $100k investment after 2 years (IRR=34.7%).

Liquidity Event – see exit.

Minimum Investment – each campaign on a funding portal has a minimum investment amount, which is the minimum amount (excluding any fees) that an investor must commit so as to participate in the crowdfunding offering.

Minimum Viable Product (MVP) – popularized in Eric Ries’ book The Lean Startup, the minimum viable product (MVP) is a bare-bones, proof-of-concept prototype of a business’ product, that has just enough features to allow the initial launch and the gathering of customer feedback for early learning.

Post-Money Valuation – the valuation of a company after any investment or financing. In equity crowdfunding, post-money valuation is the valuation after equity crowdfunding dollars are accounted for. Example: a company is raising $1M at a $5M pre-money valuation. $5M is the pre-money valuation, and $6M would be the post-money valuation ($1M+$5M).

Power Law – a power law distribution, as opposed to the common normal distribution curve, is one that has a “hockey stick” shape and decays with increasing value of x. In early-stage investing, company returns are often assumed to have power law distributions, and so understanding the importance of placing low-probability but high expected-value bets is of critical importance to succeed in early-stage investing.

Pre-Money Valuation – the valuation of a company prior to any investment or financing. In equity crowdfunding, pre-money valuation is the valuation before any of the equity crowdfunding dollars are accounted for. Example: a company is raising $1M at a $5M pre-money valuation. $5M is the pre-money valuation, and $6M would be the post-money valuation.

Return on Investment (ROI) – the return on investment (ROI) is equal to the gains of an investment divided by its initial capital investment. E.g. If an investor invests $100k and that results in a $500k exit, the ROI is ($500k-$100k)/$100k = 400% ROI. In contrast to IRR, the ROI does not take time of an investment into account.

SaaS (Software as a Service) – a Software as a Service (SaaS) company is a business that hosts a software application and provides it to users over the internet.

Product-Market Fit (PMF) – a business is said to have found product-market fit when they can demonstrate they have a great product that meets a real demand in a market. When looking at growth metrics, this is often considered the tipping point when a business no longer must “push” and market their solution to the market, but where there is substantial “pull” from the market to get more of the product. This is usually considered a prerequisite to scaling, since scaling prior to finding PMF may result in something that is not self-sustaining.

Types of Offerings

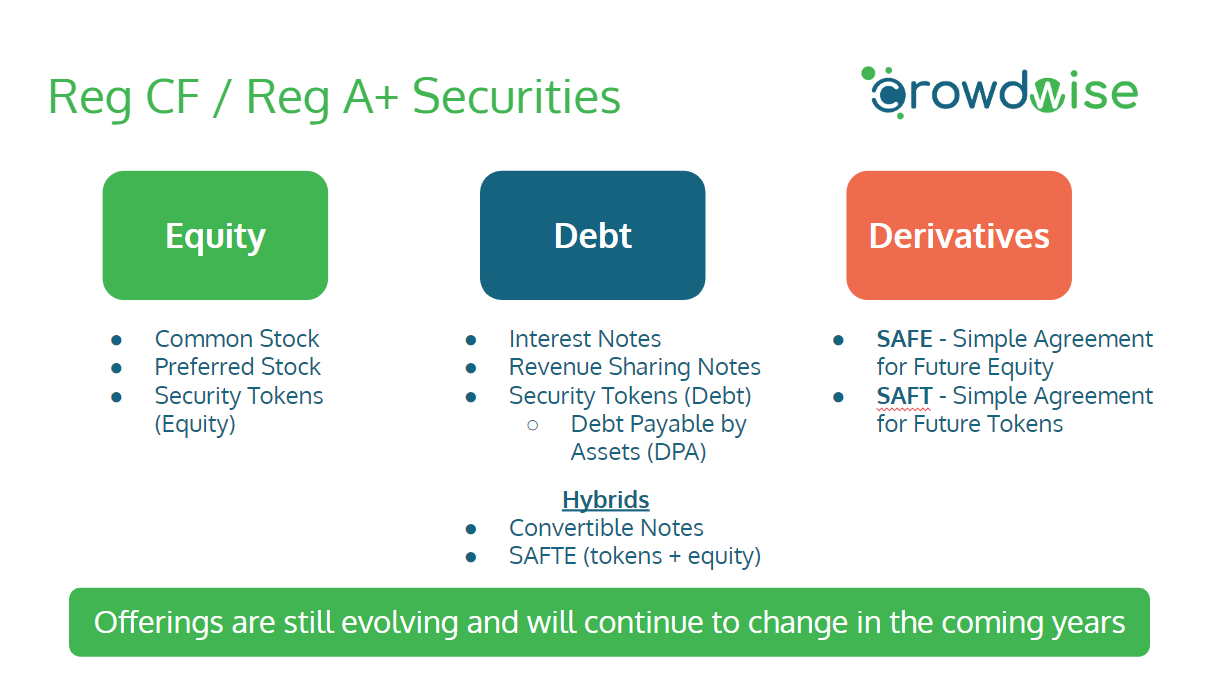

The two types of offerings that you will encounter on equity crowdfunding platforms can be broadly categorized as either equity, debt, or hybrid offerings. SAFEs could also be considered a type of derivative security, since they are more like an option/warrant, and aren’t actually equity until they convert. Below are some of the most common terms you will encounter with these deals.

Equity Offerings

Common Shares – like owning stock in a public company, common shares are typically the shares held by founders and employees of a company, and may be sold to investors to give equity in the company.

Preferred Shares – see common shares, with preferred shares also having added benefits for outside investors, such as a liquidation preference (meaning they are paid out in full prior to common shares if the company were to declare bankruptcy.)

SAFE (Simple Agreement for Future Equity) – a SAFE is a legal document, originally created by the incubator Y-Combinator, for an agreed-upon amount of future equity upon a trigger event, like a priced round (e.g. Series A). It removes the interest rate and maturity date from convertible notes and is not a formal priced round, meaning that fewer fees are incurred by the fundraising business. Note: crowdfunding SAFE terms currently vary by funding portal. For example, there are some key differences between a WeFunder SAFE and a Republic Crowd SAFE. Ensure you read the specifics of the SAFE you invest in.

Valuation Cap – a valuation cap is a limit placed on the security offering such that the investor will be granted future shares of equity at this valuation, instead of the at future round’s higher valuation. For example: if you invest $100 in a SAFE with a $5M post-money valuation cap, and during a subsequent Series A round the company sells Preferred shares at a $10M post-money valuation, you would still pay the share price at the earlier $5M valuation, effectively giving you a 50% discount from the new Series A investors (exact math will differ slightly due to dilution). Note: for SAFEs and Convertible Notes with both discount rates and valuation caps, the investor is granted the single option that grants the best price (i.e. you don’t get both a valuation cap and a discount rate).

Discount rate – in addition to valuation cap, most SAFEs and Convertible Notes will also typically have a discount rate. This is the discount that will be granted for the additional risk taken on by early investors. For example, if you invest in a SAFE with a 20% discount rate, and the follow-on Series A share price is $10/share, you will receive a 20% discount when your SAFE converts to equity, and pay $8/share for the Series A round. Note: for SAFEs and Convertible Notes with both discount rates and valuation caps, the investor is granted the single option that grants the best price (i.e. you don’t get both a valuation cap and a discount rate).

Pro-rata rights – pro-rata rights, also referred to as participation rights, provide the investor the right (but not obligation) to invest additional capital in any follow-on funding rounds to maintain the investor’s original percentage of equity ownership in the company. For equity crowdfunding investments, there is typically a pro-rata rights threshold (for example, $25,000), meaning that any capital investments below that amount will not be granted pro-rata rights.

Hybrid and Debt Offerings

Convertible Note – a convertible note is a type of hybrid equity/debt security offering – typically with an interest rate and maturity date, as well as a valuation cap and discount rate – that converts to equity upon later equity rounds of financing.

Interest rate – for convertible notes and debt offerings, the interest rate is the rate that will be paid back by the business to the investor.

Maturity Date – for convertible notes and debt offerings, the maturity date is the date upon which the note must be fully repaid to the investor, with interest, if it has not already converted to equity. In early-stage investing, maturity dates can help by offering a timeline and sense of urgency for the founders to hit their next milestones, but can also cause unnecessary stresses and premature business failures when notes come due and the startup is forced to pay back all the debt before finding product success. This is one of the reasons that Y-Combinator invested the SAFE, which does away with interest rates and maturity dates.

Revenue Sharing Note – Revenue-Sharing Notes are debt-based vehicles that pay back an interest rate (or multiple of the original investment) based on cash-flows of the business. The payments are intended to be better aligned with company revenues. This means an investor could be paid back sooner or later than a typical debt-based note, depending on the company’s cash-flows.

Token Offerings

While the initial focus of CrowdWise will be on equity deals, it would be unwise to ignore how blockchain and cryptocurrencies are also shaking up the traditional fundraising landscape. Below are some of the different token offering types that you may see when screening deals.

Coins or Tokens – in the cryptocurrency and blockchain world, instead of shares of equity, these networks may decide to issue “coins” or “tokens”. They can be thought of as shares in the company, and will typically have a value per token as well as a planned amount of tokens that will be issued. Similar to shares in a private company, unless there are secondary exchanges that come along, these coins and tokens cannot be traded as more liquid assets until a company has held its Initial Coin Offering (ICO) to the public, similar to an IPO in the equity world.

Initial Coin Offering (ICO) – analogous to an IPO in the equity world, an ICO is when a token is offered to the public for sale. This is often one type of trigger event where SAFTs would convert to tokens.

SAFT (Simple Agreement for Future Tokens) – in the blockchain token world, you can think of SAFTs as the rough equivalent of SAFEs for equity. It is intended to be low cost for the startups, and you don’t formally receive any tokens until a future ICO or other event, similar to SAFEs.

SAFTE (Simple Agreement for Future Tokens or Equity) – SAFTEs are a combination of SAFTs and SAFEs in one offering, where you can potentially receive a combination of tokens or equity in the future, dependent on trigger events.

Token DPA (Debt Payable by Assets) – a Token DPA (Debt Payable by Assets) is a new vehicle that Republic has created to replace the SAFT and provide additional protections for retail investors. Unlike SAFTs, which have no maturity date or interest rate, Token DPAs include both an interest rate and maturity date, as well as additional details about what happens if there is no future trigger event to issue tokens, or the product doesn’t materialize as planned. In very rough terms, it is more akin to how Convertible Notes offer maturity dates and interest for equity deals. Thus, you can remember the SAFT/TDPA and SAFE/Convertible Note combinations.

JOBS Act Regulations

JOBS Act – the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act, initially signed into law in 2012 under President Barack Obama, is aimed at encouraging funding and support of small businesses by updating US securities regulations (see below).

Regulation D Rule 506(c) (Reg D) – also known as Title II of the JOBS Act, Reg D Rule 506(c) offerings now allow companies to raise via general solicitation (e.g. advertise to the general public), but only to accredited investors.

Regulation Crowdfunding (Reg CF) – also known as Title III of the JOBS Act, Reg CF offerings were adopted in May 2016 and allow non-accredited investors to invest in private companies alongside accredited investors. Reg CF relaxes some other securities act filing and reporting requirements to reduce the labor burden and costs on companies utilizing Reg CF.

Regulation A+ (Reg A+) – also known as Title IV of the JOBS Act, Reg A+ allows private companies to raise up to $50M in capital, via general solicitation, to both accredited and non-accredited investors, but remain private and do it for reduced costs compared to an Initial Public Offering (IPO).

Financing Rounds

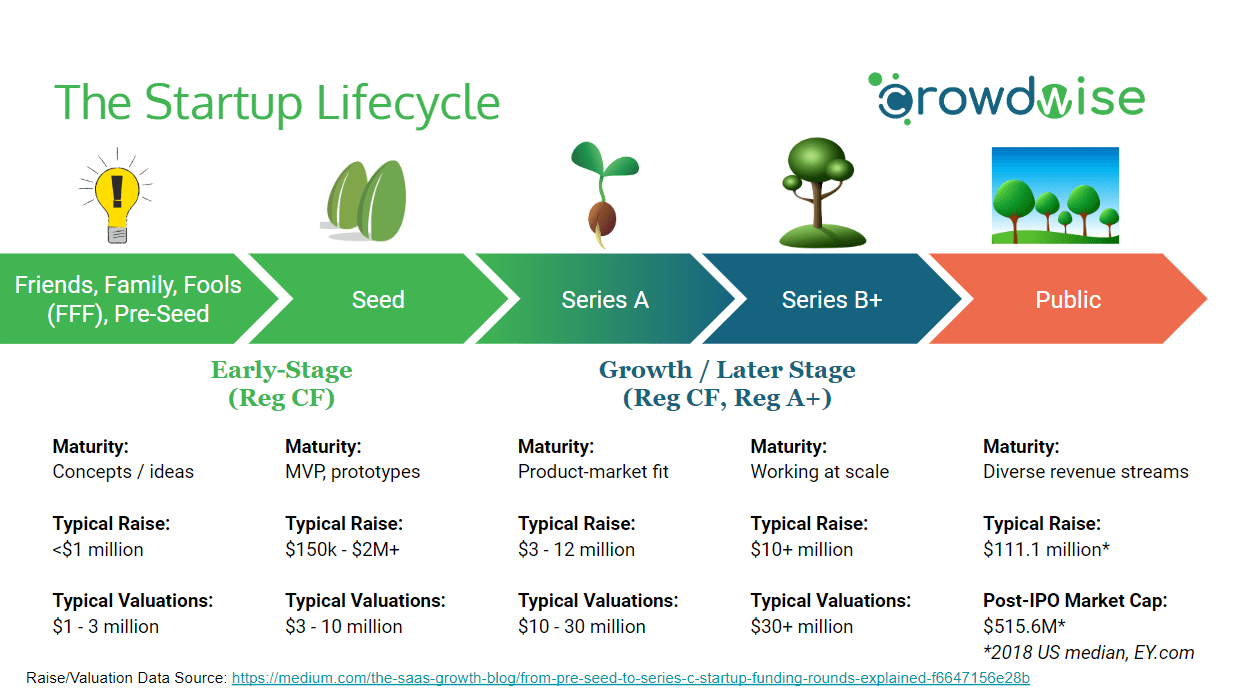

While there are no formal definitions or strict lines between various rounds of startup financing, some rough guidance is provided below to set expectations for more commonly seen rounds.

Pre-Seed – since most seed rounds typically come 2.4 years after a company is founded, these initial pre-seed funds are used to help fund the business just enough to build a product, distribute it, and gain enough traction to convince seed investors to invest. This could be capital from friends and family, Angel Investors, founders, or early-stage incubators.

Seed – a Seed round is when the first Super Angel or micro-VC funds may get involved, and where the startup has an idea or MVP, but needs capital to find product-market-fit. Typical Seed round amounts would be a $100k-$2M raise (depending whether Angels or micro-VCs are getting involved) at a $3M-10M valuation.

Bridge Round – in the event that a startup has raised Seed capital, is making solid progress, but needs a little more capital to find product-market fit, they may raise a “bridge round”. These can typically close much quicker than a full-blown Series A, and allow the startup to have a little more time to prepare for their Series A.

Series A – a Series A financing round, typically led by a lead investor (Angel or VC firm), usually demonstrates that the startup has found product-market-fit and can demonstrate strong traction and potential to grow and scale. This influx of capital is used to help scale as fast as possible since product-market-fit has been achieved. Typical Series A amounts would be a $3M-12M raise at a $10M-30M valuation.

Series B+ – after a Series A, the subsequent rounds continue increasing in total funds raised and valuation (hopefully), and could go on from Series B, to Series C, D, E, and more. The size of the rounds, due to larger VC and institutional investors getting involved, continues to increase with each round. Thus, it can be harder for even larger Angels to maintain their percentage ownership due to the capital required (e.g. owning 5% of a $5M company requires much less capital than maintaining your 5% ownership in a $500M company).

IPO – an Initial Public Offering (IPO) is a private company’s initial offering of stock to the public by being listed on public stock exchanges. It is often looked at as the holy grail for early-stage investors since the capital returns on companies that make it this far are substantial. However, the fees and regulations for being listed on a public exchange are also substantial; thus, it is typically only the large companies that have sufficient resources that will look to go through an IPO.

Startup Financials

Burn rate – the burn rate is the amount of monthly cash expenditures a startup incurs for its operations. For example, $100,000 a month. Burn rate is used to calculate a startup’s runway.

Gross-burn – the burn-rate of a company based only on monthly operating costs that are incurred is referred to as the gross-burn. It does not include any revenues produced by the company, referred to as net-burn. Example: if a company burns $50k a month in expenses and has $5k in revenue, the gross-burn is still only $50k a month.

Net-burn – the burn-rate of a company that also takes positive cash flows (revenues) into account is called net-burn. Example: if a company burns $50k a month in expenses and has $5k in revenue, the net-burn is ($50k-$5k) = $45k a month.

Runway – runway is the number of months that a business has left before it runs out of money. It is equal to (cash + revenues) / burn rate, or simply (cash / net-burn). For example, if a company has no current revenues, $1M in the bank from a Seed round, and a $100k burn rate, they have 10 months of runway ($1M + $0) / ($100k/month) = 10 months.

ARR / MRR (Annual Recurring Revenue / Monthly Recurring Revenue) – monthly recurring revenue is the amount of income from recurring sales, such as subscription services. Annual recurring revenue (ARR) is simply the MRR*12, or the past 12-months of cumulative MRR. e.g. if a company has 100 paying customers at $1k a month, their MRR is $100k, and their ARR from the current month is $1.2M.

Margin (in business) – the difference between the seller’s cost of goods sold (COGS) and the sales price (revenue), expressed as a percentage. For example, if selling a single item costs the seller $7, and they sell it for $10, the profit is $3, which is a 30% margin (margin = profit / revenue).

TAM (Total Addressable Market) – the total addressable market is the total possible demand for a product or service if 100% market share was achieved. This is larger than the serviceable available market (SAM) or the serviceable obtainable market (SOM).

Dilution – dilution is the decrease in an investor’s ownership in a company due to the company’s issuance of additional equity to new investors. In Angel Investing, dilution can be prevented by exercising pro-rata rights; however, for most equity crowdfunding deals under $25k, dilution will occur when the company raises additional funds.

Cap Table – short for capitalization table, is a summary table showing the equity percentage of ownership in the company by the founders, owners, and other investors. Cap tables are much more common to see in Angel Investing than in equity crowdfunding.

Traction – traction is proof, often via paying customers and users, that a given business solution meets a particular customer’s needs by solving a problem. Typically, traction also assumes a certain amount of geometric growth, such that a “hockey stick” shape in customers/users is present.

Revenue – a business’ revenue is the gross sales (also known as top line) prior to subtracting any operating or other expenses. For example, if a company had $1M in annual software sales to customers, the annual revenue would be $1M, prior to accounting for any expenses to arrive at profit (bottom line).

Profit (also known as bottom line) – profit is the surplus remaining after total costs are deducted from total revenue.

Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) – the Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) is the per-user cost for the company to market and attract a new customer. It is the total marketing and acquisition budget spent, divided by the number of new customers gained, over a specified time period. For example, if a company has spent $10k and resulted in 1000 new paying customers in the past month, the CAC would be $10k/1000 = $10.

Lifetime Total Value (LTV) – the Total Lifetime Value (TLV), sometimes called the Customer Lifetime Value (CLV), is an estimate of the average amount each new customer will spend with the company over the time period that they are expected to remain a paying customer. This would include multiple purchases of different products, remaining a paying subscriber for a number of months, etc.

TLV:CAC ratio – after knowing the TLV and CAC, investors can calculate the TLV:CAC ratio, which is an indication of whether it is profitable to invest additional capital in acquiring new customers, or if the business is losing money in trying to acquire customers using the current assumptions. Some investors look for a TLV:CAC ratio of around 3:1. They consider 1:1 as you are spending too much (each $1 invested is only resulting in $1 of sales), and a value of 5:1 as spending too little (each $1 invested is returning $5).

Monthly Active Users (MAU) / Daily Active Users (DAU) – a measure of how many active users over a given time period, either daily or monthly, that are using a given product. This is typically one metric, when looking at its growth rate, that can inform the investor of whether a product has traction and achieved product-market-fit or not.

Churn – the opposite of customer retention rate, churn (or customer attrition) is the percentage of subscribers that terminate their subscription within a given timeframe. For example, if during the month of January a startup had 100 paying customers and 20 did not renew their subscription, their churn would be 20/100 = 20%. For a non-subscription business, it could be considered the number of customers that do not make a repeat purchase.

Retention Rate – the opposite of churn, retention rate is the number of customers that remain loyal and paying to the business. It is typically a good measure of how well a given solution is meeting a customer’s need. For example, if you had 100 customers total, and 80 customers from the prior month returned and placed a second order in the current month, the retention rate would be 80/100 = 80%. For a SaaS subscription product, it would be the number of users that renew their subscription in a given time period.

Types of Investors

Accredited Investor – according to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Rule 501 of Regulation D, an accredited investor is anyone that makes more than $200k per month for the past two years ($300k joint earnings with a spouse), or has a net worth exceeding $1 million, excluding any primary residence. There are also guidelines for professional qualifications that allow some professional investors to be deemed accredited investors.

Non-Accredited Investor – (also: un-accredited investor) – according to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Rule 501 of Regulation D, a non-accredited investor is anyone who doesn’t meet the definition for an accredited investor. Until recently, only accredited investors could invest in private companies, which has changed with Regulation CF of the JOBS Act.

Friends and Family – typically, prior to a Seed round, a startup may be financed by friends and family of the founders, to help give the idea enough capital to show potential seed investors that there is promise in the business.

Crowdfund Investor – due to the JOBS Act, both accredited and non-accredited investors can now invest as crowdfund investors through online funding portals. Similarly, certain websites, like AngelList, may provide a means for accredited investors to invest alongside a group of other investors, typically led by a “lead” Angel investor who handles most of the due diligence, valuation, and other interactions between the founders and the investors.

Angel Investor – an Angel Investor is any investor that invests their own capital in early-stage companies they believe in. They typically get involved earlier than most VC funds, when a company may only have an idea or little traction, and give the startups a chance to bring their product to market. Many VC funds must invest larger amounts of capital and have stricter requirements for proven traction, sales, etc., and so these earliest investors that take a higher risk on the entrepreneurs are referred to as “Angels”.

Venture Capital (VC) – as opposed to Angel Investors, Venture Capital (VC) firms are professional investors that invest other people’s money. They are paid via something commonly called the 2-20 rule, where they are given a set 2% fee based on the assets under management (AUM), and then a 20% bonus “carry” where they share in any profits they make for their clients. VC firms typically aim to control a certain amount of a company (e.g. 10%) at each round, and thus invest much higher amounts of capital on average than Angels.

Types of Companies

Unicorn – a unicorn is any company that reaches a $1 billion valuation, either in private or public markets. These “mythical creatures” are the goal of venture capital investments, since a $1B+ valuation implies significant returns for early-stage investors at valuation of $5M, $50M, even $100M.

Decacorn – even more rare than a unicorn, a decacorn is any company that reaches a $10B+ valuation in either the private or public markets.

Super-Unicorn – the rarest breed, a super-unicorn is a company that reaches $100B+ valuation, such as Facebook. The earliest investors in these companies are the legends of startup investing.

Zombie – like the undead being for which it is a named, a zombie firm in the early-stage investing world is a business that has not failed and continues to operate, but is not going anywhere, cannot raise capital, and does not provide any exits (or returns) for their investors.

Startup – a startup business, as opposed to a lifestyle business, is a new business focused on maximizing growth. Simply being a new small business is insufficient to qualify as a startup, since startups are designed for maximum growth.

Lifestyle business – a lifestyle business, in contrast to a startup, is a business built around providing its founders with a more balanced lifestyle and work-life balance, and may not be focused solely on maximizing growth.

[…] Another excellent reference for equity crowdfunding terms is here. […]