Valuation of Early-Stage Startups – Does it Matter? (Part 1)

A common term that crowdfunding investors will come across when looking at startups is valuation. What is valuation? Does valuation really matter for early-stage investors and angels? Is valuation more of an art or a science?

In Valuation Part 1, we will investigate all these questions and hear what some notable investors think about valuation. In Valuation Part 2, we will talk about the top six methods for valuing early-stage startups and walk through how valuation works on crowdfunding portals.

http://crowdwise.org/all/top-6-methods-for-valuing-startups-valuation-part-2/

What is valuation?

Valuation (of a startup) is the present market value, as agreed upon by founders and investors.

Valuation of an early-stage business depends on many factors, such as:

- The founder(s)

- The team

- Intellectual Property (e.g. patents and proprietary technology)

- State of the product (idea, prototype, first iteration, etc.)

- Customers (both current and future potential)

- Traction and growth

- Sales and margins

- Risks

- Competition

- Industry (current and future potential)

- Supply and demand among investors

- And much more…

Public vs. Private Market Valuation Differences

For investors who are familiar with the public markets, a startup’s valuation is similar to the market capitalization of public companies.

Early-stage startups are different in that instead of having a liquid supply and demand of shares among millions of potential investors, there are typically only a few investors in early-stage businesses. It’s also much harder to buy and sell shares, since secondary markets are still being developed in equity crowdfunding. Thus, the market for early-stage equity shares is inefficient; that means it is possible to either get a bargain or to overpay.

In addition, a startup’s valuation is dependent on many more factors that can’t easily be measured. Thus, valuation depends more on subjective criteria rather than objective criteria.

While every company on Wall Street has years of financials that are constantly scrutinized by countless analysts, early-stage businesses may have a very limited (or even non-existent) operating history.

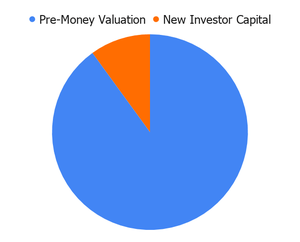

Pre-Money vs. Post-Money Valuation

Investors in startups should know the difference between pre-money and post-money valuations.

- Pre-money valuation is the valuation of a business before the current round (i.e. not including investors’ new money in the round).

- Post-money valuation is the valuation of a business after the current round (i.e. including investors’ new money in the round).

Thus, the relation between pre- and post-money can be expressed as:

Pre-Money Valuation + New Money from Round = Post-Money Valuation

Examples:

- Raising $200,000 at a $2 million pre-money valuation implies a $2.2 million post-money valuation ($200k + $2M = $2.2M)

- Selling 10% of a $4 million post-money valuation means raising $4M*10% = $400k (and a $3.6M pre-money valuation)

In considering pre- vs. post-money valuations, neither one is good nor bad. Investors should simply understand what is being offered so they can calculate their percent ownership correctly.

That is because an investor’s ownership depends on post-money valuation.

How to calculate an investor’s percentage ownership in a startup

An investor’s percentage ownership of a startup based on a given investment is calculated using:

Percentage Ownership = Investment Amount / Post-Money Valuation

For example, assume:

- The business is raising $400k at a $1.6M pre-money valuation

- You invest $1,000 in Common Shares

- How much do you own?

- First, determine post-money valuation: $400k + $1.6M = $2.0M

- Second, divide your investment by step 1: $1,000 / $2,000,000 = 0.05% ownership

- What if the business was raising the same $400k, but at a $1.6M post-money valuation?

- $1,000 / $1,600,000 = 0.0625% ownership

- You would own 25% MORE than the pre-money case

Deal terms are typically listed as pre-money valuation, since the amount that they raise in a given round cannot be known in advance. However, some financial securities may be offered with post-valuation terms. Whether a deal is pre-money or post-money will be noted in the deal terms being offered.

Is Startup Valuation an Art or a Science?

Since early-stage startups have less information and operating history on which to value their potential market value, startup valuation is often cited as being more of an art than a science.

That doesn’t mean investors pick a random number out of a hat, though.

To understand more about early-stage valuation, let’s listen to what two prominent early-stage investors – Paul Graham and Jason Calacanis – have to say about valuation.

“When someone buys shares in a company, that implicitly establishes a value for it. If someone pays $20,000 for 10% of a company, the company is in theory worth $200,000. I say “in theory” because in early stage investing, valuations are voodoo. As a company gets more established, its valuation gets closer to an actual market value. But in a newly founded startup, the valuation number is just an artifact of the respective contributions of everyone involved.” – Paul Graham, Co-Founder – Y-Combinator

Next, according to Jason Calacanis:

“Startup valuations are not science, but they’re not magic either. It’s a bit of alchemy, combined with bizarre marketplace dynamics like famous founders getting 3x the price for half the traction…” – Jason Calacanis

Jason has a traction vs. valuation matrix that visually depicts his interpretation of an “average” startup valuation, as well as what factors can cause a startup to go above or below that average (e.g. founders with past successful exits).

Human Psychology – a major valuation driver

As both PG and J-Cal imply, valuation is dependent on supply and demand. And with any system that depends on human factors, this means that valuations are inherently dependent on human psychology, behavior, and biases.

For example, when trends such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), quantum computing, self-driving cars, cannabis, blockchain, or whatever of the hot industry of the day is comes along, investors may be more eager to put money into them. Thus, an increase in demand (by investors) means that founders can (and do) command higher valuations.

And while it hasn’t been a major problem yet with Regulation Crowdfunding (Reg CF), the maximum limit of $1.07 million during a crowdfunding campaign does mean that shares could sell out and drive fear of missing out (FOMO) and other related behavior.

On the contrary, seemingly boring industries may not attract as much attention from investors. And while it may be for good reasons (e.g. a limited upside) most of the time, there will still be exceptions to this rule that prove venture capitalists wrong.

Thus, it’s important to keep in mind not only how tangible factors influence valuation, but how human psychology and investor behavior also influence trends in valuation, just as they do in public markets.

Why is valuation important (or is it)?

So valuation is part art and part science. But is valuation important for early-stage investors?

Here is a great quote from Howard Marks’ book Mastering the Market Cycle that talks to value in general:

“It’s not what you buy that determines your results, it’s what you pay for it. And what you pay—the security’s price and its relationship to intrinsic value—is determined by investor psychology and the resulting behavior.” -Howard Marks

This couldn’t be more true in many instances – but also more wrong in certain early-stage cases. Let’s consider two examples now to see when and if valuation is important.

Valuation is important – in most investments

I’m a firm believer that in most instances, valuation is crucial. Whether that is investing in public market stocks, bonds, real estate, or other securities, it’s crucial to understand the value of what you are buying to ensure that you aren’t overpaying.

However, the power-law nature of startup returns throws a wrench in the gear of this equation. As stated by Peter Thiel and demonstrated with early-stage crowdfunding data, the majority of early-stage investment returns will be generated by very few of the portfolio’s investments.

What does this mean for you as an early-stage investor?

It means that if you optimize for valuation, you could potentially miss out on those one or two investments that make all the difference for your portfolio.

Let’s take a look at Uber as a case study of what happens if you optimize for valuation instead of optimizing for potential home runs for your portfolio.

Valuation is less important (but far from worthless) in home run investments

Consider the case of Uber’s early investors, such as Jason Calacanis, in Uber’s 2010 seed round.

Most investors – including Mark Cuban, as well as 150 of 165 AngelList investors – passed at a $5.4 million post-money valuation because it looked too expensive at the time.

In an email that Mark Cuban sent to Uber CEO Travis Kalanick, he said “I wouldn’t touch a 2mm valuation, let alone 5mm.”

Hindsight is always 20/20, but in his overall portfolio, do you think it would have mattered if Mark Cuban invested at a $5 million valuation instead of at $2 million? What about a $20 million or $60 million valuation?

This is where the magnitude of power laws comes in and where the human brain fails to grasp the implications of those power law returns.

Assuming 50% dilution from the 2010 seed round until IPO, and $70 billion as the closing sale price on day one of Uber’s IPO, here are the potential exit multiples investors would have realized at each valuation:

As you can see, even if Uber had been asking for $60 million, as they did in their Series A, it still would have resulted in roughly 600x returns. That’s enough to make any portfolio a winner.

Initial Valuation | IPO Exit Multiple |

$5.4M (actual) | 6,481x |

$10M | 3,500x |

$20M | 1,750x |

$60M (Series A) | 583x |

This isn’t to say that the difference between 6,000x+ returns and 3,500x returns is insignificant; obviously you want the best you can get, and valuation does impact those returns. The point is not to be blinded by valuation and optimizing for the wrong thing.

The biggest mistake early-stage investors can make is optimizing for valuation instead of optimizing for home run potential

I refer to this as the valuation optimization fallacy for early-stage investing.

Arguing with founders over a few million in valuation (e.g. you decide not to invest at $6 million because you think they are only worth $4 million) is entirely missing the point of early-stage investing. The potential for high rewards means that you will have to take some big risks. If you’re investing not to lose instead of playing to win, then you’ve already set yourself up for failure.

This does not mean that you should throw money at every startup that comes along promising to be the future. Discovering where that threshold is and how to pick winning founders and startups is all part of the journey.

The Valuation Optimization Fallacy in Equity Crowdfunding

Many experienced investors, probably including names like Warren Buffett, would likely take issue with the prior assertion that early-stage investors shouldn’t optimize for valuation (although Buffett has recently entered the startup investing space himself).

So how would this approach have fared thus far in Regulation D equity crowdfunding?

On WeFunder’s results page, two of the top four performing Reg D WeFunder investments to date were on Uncapped SAFEs.

An Uncapped SAFE means kicking the valuation can down the road, and means there is no cap at which they convert. The SAFE’s discount rate and valuation cap are often benefits that early-stage investors expect for taking additional risk by investing so early. An Uncapped SAFE is essentially the same as flipping the bird to anyone who cares about getting the best possible valuation, saying, “Nah, we’ll figure that out later.”

However, if you had excluded those deals (due to the lack of valuation), you would have missed out on two of the best-performing Reg D WeFunder investments to date.

As with most things in the investment world, there are both pros and cons to Uncapped SAFEs. Recently, WeFunder has transitioned to a Most-Favored Investor (MFI) clause SAFE, which means you get the best deal terms that any subsequent investor gets, but again avoiding the question of valuation in the current round.

Thus, there isn’t a simple answer to the question “does valuation matter?”. As with anything, it must be taken on a case by case basis, but investors should also keep the bigger picture in mind (i.e. not falling victim to the valuation optimization fallacy and missing potential home run investments).

Summary – Introduction to Valuation

To sum up this introduction to valuation:

- Valuation matters, but what’s more important is not missing out on a potential home run (i.e. the valuation optimization fallacy)

- This goes back to Peter Thiel’s rule – “…only invest in the companies that have the potential to return the value of the entire fund.”

- Valuation is part art, part science

- It depends on many things, ranging from current market conditions, to founder’s past record, team, IP, traction, risks, geographical location, competition, and more

- Post-Money Valuation = Pre-Money + Total $ Raised

- Post-Money Valuation = Total $ Raised / Percent of Equity

- Investor’s Ownership = Investment Amount / Post-Money Valuation

In Valuation Part 2, we will discuss the top six methods for how to value startups. We will also cover how investors put all the methods together and how valuation works on equity crowdfunding portals.

Responses