What are Direct Public Offerings (DPOs)?

The world of financial securities can be confusing. That is one reason the SEC has been looking at suggestions for harmonizing existing securities regulations. Exempt vs. non-exempt offerings, numerous regulations, and overlapping vocabulary leads to confusion for both startups (i.e. issuers) and investors.

Today, we will demystify some of the confusion around one term that encompasses a large number of these regulations and is often thrown around without a solid understanding of what it means. I’ve seen it pop up in more and more finance articles, and yet authors don’t seem to use it consistently.

This term is a Direct Public Offering (DPO).

What are Direct Public Offerings (DPOs)?

In the most general sense, a Direct Public Offering (DPO) is when an issuer (i.e. company) sells securities directly to investors, without going through a regulated intermediary or third party (i.e. a Reg CF funding portal, or an underwriting firm such as an investment bank or broker-dealer).

A DPO is not an official term in the eyes of the SEC.

Unfortunately, because a DPO isn’t an official term, I’ve seen it used to describe everything ranging from smaller private direct offerings (e.g. Reg D Rule 504, Reg A+, intrastate offerings) all the way to much larger direct listings on national exchanges.

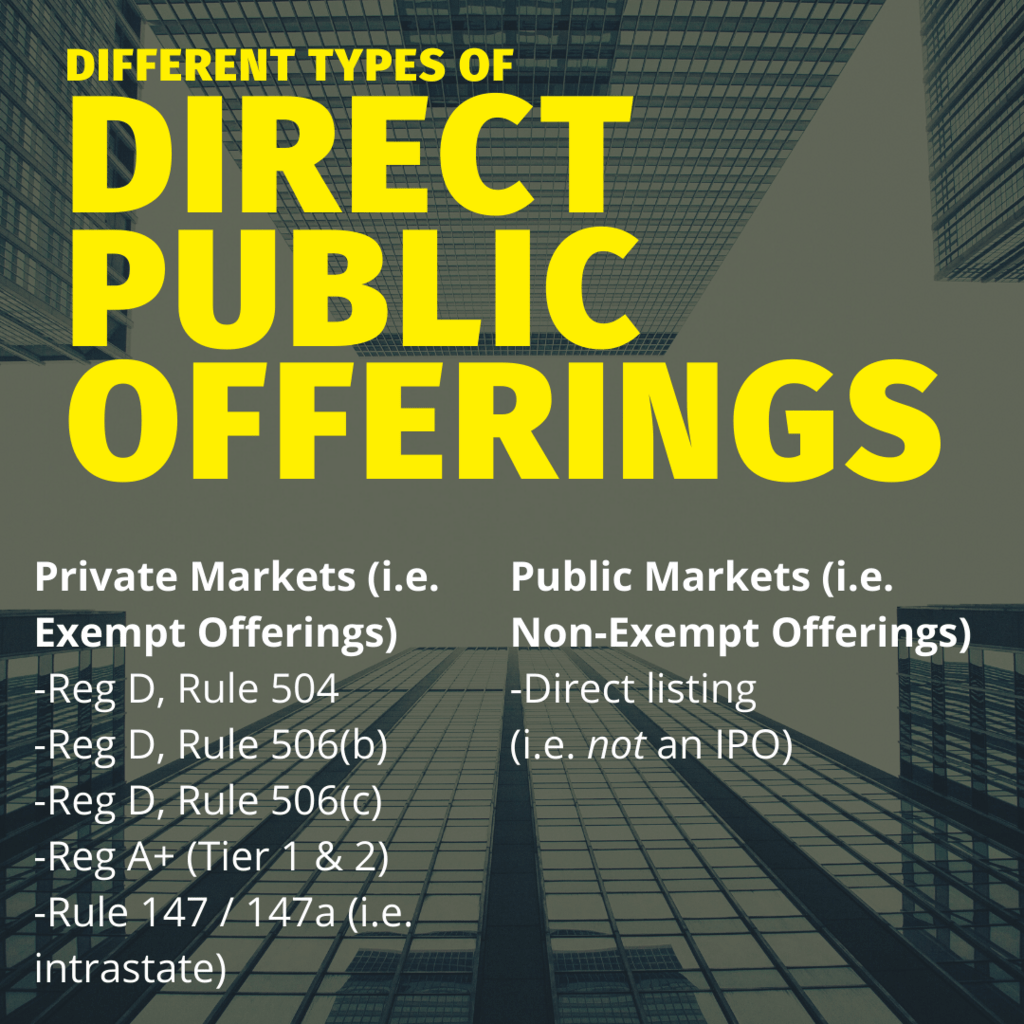

Types of DPOs

As we’ll cover in more detail below, the term DPO can be used to describe the sales of securities in both the public (i.e. non-exempt) and private (i.e. exempt) markets. This often leads to confusion when trying to learn about DPOs, since most websites only focus on either the public- or private-market definition.

The most common methods for doing a DPO are:

- Non-exempt offerings

- Direct Listing (not an IPO) on a public exchange – e.g. Slack and Spotify

- Exempt offerings (SEC has an excellent comparison matrix here)

- Reg D Rule 504

- Reg D Rule 506(b) and 506(c)

- Reg A+ (Tier 1 and Tier 2) – e.g. Fundrise’s iPO

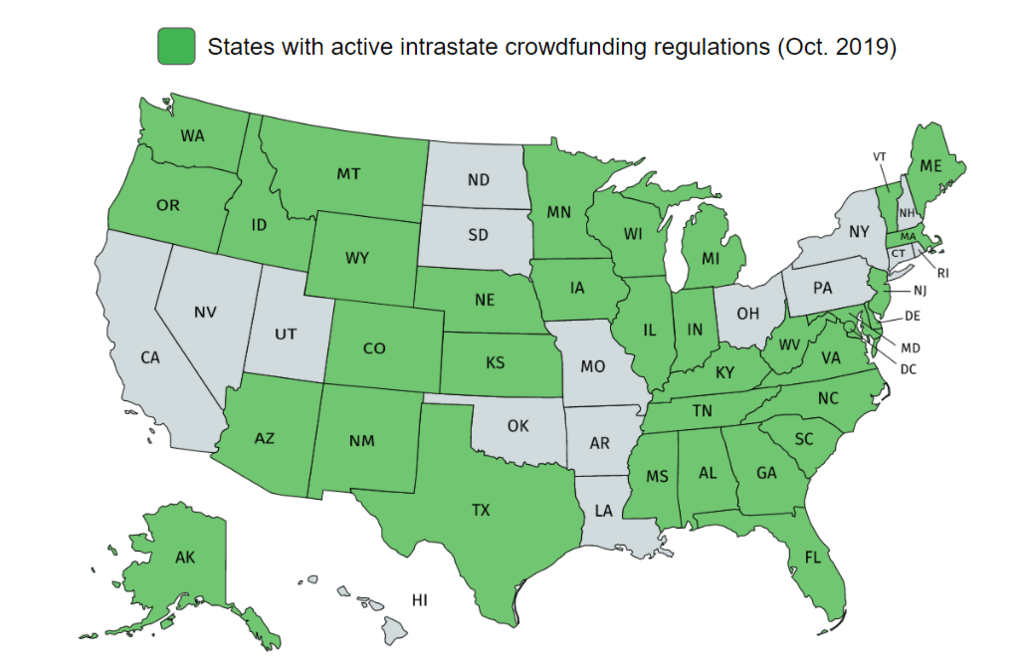

- Rule 147 and 147a (Intrastate Crowdfunding)

Some of the above exempt offerings, such as Reg A+, Reg D and some intrastate crowdfunding offerings may use an intermediary, but do not always require it, and thus can be one form of a DPO. In contrast, Reg CF and some states require the issuer to use registered funding portals and/or broker-dealers, and thus are not types of DPOs (since they use a third-party intermediary).

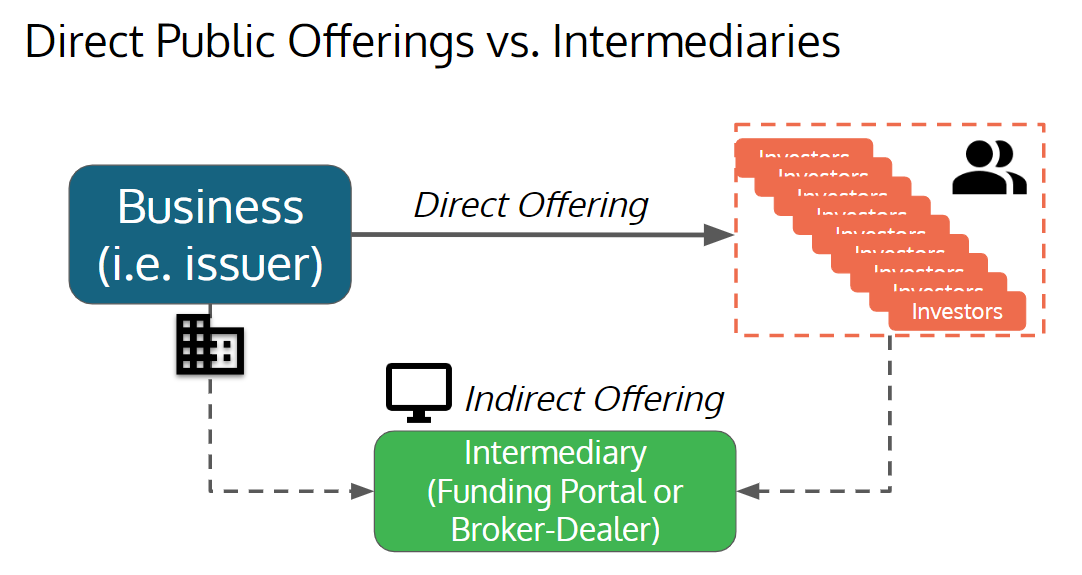

Indirect vs. Direct Offerings

To better grasp DPOs, one should understand the two high-level ways that issuers sell securities to investors.

First, the issuer may use an intermediary, which is an independent third-party, that acts as the middle-man between the issuer and investors. With exempt offerings such as Regulation Crowdfunding, this may be a funding portal or registered broker-dealer. In non-exempt offerings in the public markets, these third parties are underwriting firms, such as investment banks and broker-dealers.

If the issuer does not use an intermediary and instead sells directly to investors without a middle-man, that is what is typically referred to as a DPO.

Public vs. Private Markets (Non-Exempt vs. Exempt Offerings)

While DPO has “public” as part of its name, it’s important to make the distinction between what is traditionally referred to as the public vs. the private markets, and what a DPO means in each context.

The private markets are generally offerings that use one of many securities exemptions, such as Reg D, Reg A+, Reg CF, and intrastate offerings. Note that many of these offerings can still sell and advertise to the public; however, the shares are not as liquid as those of shares listed on public exchanges, they are not as widely-available or widely-held by investors, they are exempt from registration with the SEC and/or states, and the ongoing reporting requirements (if any) are fewer. Thus, these typically fall under the “private market” umbrella.

In contrast, shares that are listed on national exchanges (e.g., NASDAQ or NYSE) are what investors often refer to as the public markets. These are much more widely-held by investors, are more easily traded and are more liquid, have ongoing reporting requirements under the 1934 Exchange Act, and are registered with the SEC (i.e non-exempt from registration under the 1933 Securities Act). Thus, they are commonly referred to as the “public markets”.

In the case of DPOs, it’s important to note that both of the above are technically offered to the public in some way. There are key differences between DPOs when referring to the public vs. private markets, though.

Public Market DPOs vs IPOs

The most common way that businesses raise capital in the public markets is by doing an Initial Public Offering (IPO). In an IPO, the company partners with underwriting firms, such as an investment bank or a broker-dealer. The issuer raises capital from the sale of newly issued securities and existing investors are diluted.

An underwriting firm (e.g. Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Goldman Sachs) helps to market and sell the securities in an IPO. In compensation for this help, these firms get paid a fee based on the sales of those securities, which can be upwards of 4-7%.

Thus, some businesses, such as Spotify (2018) and Slack (2019), have chosen to do direct listings. In doing a direct listing, the company is still listed on a national exchange, but without the use of a third-party underwriter. Thus, fees are much lower, and there are other benefits (such as no lockup period and no dilution for existing investors, since there is no creation of new shares).

It is this second case, the direct listing, which is sometimes referred to as a Direct Public Offering (DPO) in the public markets.

Private Market DPOs

For less-mature companies, there are numerous exemptions when raising capital in the private markets, which help to reduce the costs and administrative burdens compared to going public. Certain exemptions, such as Regulation Crowdfunding, require the use of a third-party intermediary (i.e. a funding portal or broker-dealer), and would not be called a direct public offering.

Other exempt security offerings may allow the sale of securities directly to the public, instead of through an intermediary. These include:

- Reg D Rule 504

- Reg D Rule 506(b) and 506(c)

- Reg A+ (Tier 1 and Tier 2)

- Rule 147 and 147a (Intrastate Crowdfunding)

While the above regulations permit the direct sale of securities to the public, some of those regulations may still permit the use of an intermediary (such as Reg D and Reg A+ sales, as seen on many of the crowdfunding portals such as WeFunder, StartEngine, etc.).

Summary of Direct Public Offerings (DPOs)

As startup investors can see, DPO may refer to numerous different ways of raising capital depending on the context.

What are the pros and cons of using DPOs vs. other methods of raising capital, such as IPOs or Regulation Crowdfunding?

For the issuing company, one advantage is that a DPO may have a lower cost of capital due to fewer fees paid to intermediaries or other third parties. This is especially true when direct listing on the public markets vs. doing an IPO.

However, the fees and administrative burdens (legal, accounting, filing, disclosure, etc.) are very much dependent on the type of DPO. For example, some direct offerings using Reg A+ Tier I may require an issuer to register with every single state in which it wishes to offer and sell securities, which can quickly become burdensome and costly.

By avoiding the use of an intermediary, companies may have more control and flexibility over their security offering. This means they may have more control over their marketing and branding, even allowing investors to invest directly on the issuer’s own website, such as the Fundrise internet Public Offering (iPO).

The potential downside of this flexibility is that there are far more opportunities for issuers to overlook key aspects of securities sales. This could land them in potential regulatory and legal trouble with the SEC and/or states. Intermediaries, on the other hand, are FINRA-registered and regulated by the SEC, and thus have more well-defined processes and guidelines for helping issuers that raise capital on their websites.

Investors should always be much more thorough in their due diligence and wary of offerings being made directly to the public vs. being done through an intermediary. The potential for fraud is far higher for DPOs done outside of regulated intermediaries. On regulated intermediaries, investors at least know that issuers have undergone a minimal amount of anti-fraud, bad-actor checks and due diligence to be listed.

DPOs are simply another name for the various ways that startups can raise capital from the crowd.

By learning the nuances of DPOs, you are now better prepared to understand the different types of offerings in both the public and the private markets.

[…] of third-party platforms: They can raise funds directly by appealing to their communities through a Direct Public Offering (DPO). For example, TechSoup, a nonprofit network of NGOs that provide tech products and services to […]

[…] “direct listing” means. In short, a direct listing, also sometimes referred to as a direct public offering, is an offering in which an issuer raises capital directly from investors without a third-party […]